Page 195 - Read Online

P. 195

Page 8 of 11 Kolokotronis et al. Mini-invasive Surg 2021;5:19 https://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2574-1225.2021.07

Table 5. Risk factors for survival after abdomino-thoracic resection for esophageal cancer-multivariate analysis

Cox regression

Parameter

OR (95%CI) P value

Type of anastomosis 0.165 (0.067-0.409) < 0.001***

UICC tumor stage 1.371 (1.130-1.663) 0.001***

***P < 0.001. OR: Odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; UICC: Union international contre le cancer.

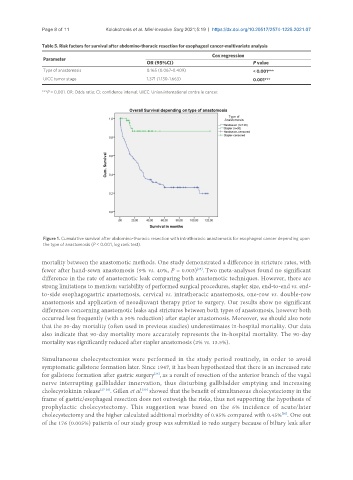

Figure 1. Cumulative survival after abdomino-thoracic resection with intrathoracic anastomosis for esophageal cancer depending upon

the type of anastomosis (P < 0.001, log rank test).

mortality between the anastomotic methods. One study demonstrated a difference in stricture rates, with

fewer after hand-sewn anastomosis (9% vs. 40%, P = 0.003) . Two meta-analyses found no significant

[25]

difference in the rate of anastomotic leak comparing both anastomotic techniques. However, there are

strong limitations to mention: variability of performed surgical procedures, stapler size, end-to-end vs. end-

to-side esophagogastric anastomosis, cervical vs. intrathoracic anastomosis, one-row vs. double-row

anastomosis and application of neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery. Our results show no significant

differences concerning anastomotic leaks and strictures between both types of anastomosis, however both

occurred less frequently (with a 50% reduction) after stapler anastomosis. Moreover, we should also note

that the 30-day mortality (often used in previous studies) underestimates in-hospital mortality. Our data

also indicate that 90-day mortality more accurately represents the in-hospital mortality. The 90-day

mortality was significantly reduced after stapler anastomosis (2% vs. 13.5%).

Simultaneous cholecystectomies were performed in the study period routinely, in order to avoid

symptomatic gallstone formation later. Since 1947, it has been hypothesized that there is an increased rate

[26]

for gallstone formation after gastric surgery , as a result of resection of the anterior branch of the vagal

nerve interrupting gallbladder innervation, thus disturbing gallbladder emptying and increasing

[30]

cholecystokinin release [27-29] . Gillen et al. showed that the benefit of simultaneous cholecystectomy in the

frame of gastric/esophageal resection does not outweigh the risks, thus not supporting the hypothesis of

prophylactic cholecystectomy. This suggestion was based on the 6% incidence of acute/later

[30]

cholecystectomy and the higher calculated additional morbidity of 0.95% compared with 0.45% . One out

of the 176 (0.005%) patients of our study group was submitted to redo surgery because of biliary leak after