Page 39 - Read Online

P. 39

Padilla et al. Rare Dis Orphan Drugs J 2023;2:27 https://dx.doi.org/10.20517/rdodj.2023.38 Page 3 of 13

system had its origin in Metro Manila when collaborators from 24 hospitals in Metro Manila developed

incidence data for six disorders that were thought to be of sufficient prevalence to justify NBS: congenital

hypothyroidism (CH); congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH); galactosemia (GAL); phenylketonuria (PKU);

homocystinuria (HCY); and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PDD). Leadership for this

PNBSP was provided by two pediatricians from the University of the Philippines Manila who were

passionately interested in NBS. Funding came from a small break-even fee (approximately US$ 11) charged

to each patient, with billing to individual hospitals based on the number of specimen collection cards

requested. Through professional contacts, collaborative laboratory services were obtained from the NBS

laboratory in Sydney, Australia. For the first year of the project, dried blood spot (DBS) specimens were

[13]

transported daily to Sydney while data accumulated and local laboratory capabilities developed . This

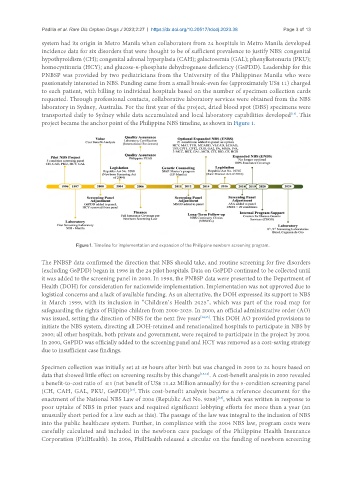

project became the anchor point of the Philippine NBS timeline, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Timeline for implementation and expansion of the Philippine newborn screening program.

The PNBSP data confirmed the direction that NBS should take, and routine screening for five disorders

(excluding G6PDD) began in 1996 in the 24 pilot hospitals. Data on G6PDD continued to be collected until

it was added to the screening panel in 2000. In 1998, the PNBSP data were presented to the Department of

Health (DOH) for consideration for nationwide implementation. Implementation was not approved due to

logistical concerns and a lack of available funding. As an alternative, the DOH expressed its support to NBS

in March 1999, with its inclusion in “Children’s Health 2025”, which was part of the road map for

safeguarding the rights of Filipino children from 2000-2025. In 2000, an official administrative order (AO)

was issued, setting the direction of NBS for the next five years [14,15] . This DOH AO provided provisions to

initiate the NBS system, directing all DOH-retained and renationalized hospitals to participate in NBS by

2000; all other hospitals, both private and government, were required to participate in the project by 2004.

In 2000, G6PDD was officially added to the screening panel and HCY was removed as a cost-saving strategy

due to insufficient case findings.

Specimen collection was initially set at 48 hours after birth but was changed in 2000 to 24 hours based on

data that showed little effect on screening results by this change [15,16] . A cost-benefit analysis in 2000 revealed

a benefit-to-cost ratio of 4:1 (net benefit of US$ 11.42 Million annually) for the 5-condition screening panel

[17]

(CH, CAH, GAL, PKU, G6PDD) . This cost-benefit analysis became a reference document for the

enactment of the National NBS Law of 2004 (Republic Act No. 9288) , which was written in response to

[18]

poor uptake of NBS in prior years and required significant lobbying efforts for more than a year (an

unusually short period for a law such as this). The passage of the law was integral to the inclusion of NBS

into the public healthcare system. Further, in compliance with the 2004 NBS law, program costs were

carefully calculated and included in the newborn care package of the Philippine Health Insurance

Corporation (PhilHealth). In 2006, PhilHealth released a circular on the funding of newborn screening