Page 103 - Read Online

P. 103

Jaswant et al. One Health Implement Res 2024;4:15-37 https://dx.doi.org/10.20517/ohir.2023.61 Page 23

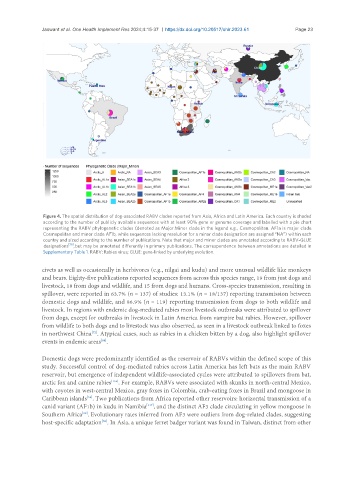

Figure 4. The spatial distribution of dog-associated RABV clades reported from Asia, Africa and Latin America. Each country is shaded

according to the number of publicly available sequences with at least 90% gene or genome coverage and labelled with a pie chart

representing the RABV phylogenetic clades (denoted as Major.Minor clade in the legend e.g., Cosmopolitan. AF1a is major clade

Cosmopolitan and minor clade AF1b, while sequences lacking resolution for a minor clade designation are assigned “NA”) within each

country and sized according to the number of publications. Note that major and minor clades are annotated according to RABV-GLUE

designations [15] , but may be annotated differently in primary publications. The correspondence between annotations are detailed in

Supplementary Table 1. RABV: Rabies virus; GLUE: gene-linked by underlying evolution.

civets as well as occasionally in herbivores (e.g., nilgai and kudu) and more unusual wildlife like monkeys

and bears. Eighty-five publications reported sequences from across this species range, 19 from just dogs and

livestock, 18 from dogs and wildlife, and 15 from dogs and humans. Cross-species transmission, resulting in

spillover, were reported in 63.7% (n = 137) of studies: 13.1% (n = 18/137) reporting transmission between

domestic dogs and wildlife, and 86.9% (n = 119) reporting transmission from dogs to both wildlife and

livestock. In regions with endemic dog-mediated rabies most livestock outbreaks were attributed to spillover

from dogs, except for outbreaks in livestock in Latin America from vampire bat rabies. However, spillover

from wildlife to both dogs and to livestock was also observed, as seen in a livestock outbreak linked to foxes

[72]

in northwest China . Atypical cases, such as rabies in a chicken bitten by a dog, also highlight spillover

events in endemic areas .

[84]

Domestic dogs were predominantly identified as the reservoir of RABVs within the defined scope of this

study. Successful control of dog-mediated rabies across Latin America has left bats as the main RABV

reservoir, but emergence of independent wildlife-associated cycles were attributed to spillovers from bat,

arctic fox and canine rabies . For example, RABVs were associated with skunks in north-central Mexico,

[116]

with coyotes in west-central Mexico, gray foxes in Colombia, crab-eating foxes in Brazil and mongoose in

Caribbean islands . Two publications from Africa reported other reservoirs: horizontal transmission of a

[56]

canid variant (AF1b) in kudu in Namibia , and the distinct AF3 clade circulating in yellow mongoose in

[117]

[62]

Southern Africa . Evolutionary rates inferred from AF3 were outliers from dog-related clades, suggesting

host-specific adaptation . In Asia, a unique ferret badger variant was found in Taiwan, distinct from other

[52]