Page 103 - Read Online

P. 103

Jones et al. Microbiome Res Rep 2024;3:24 https://dx.doi.org/10.20517/mrr.2023.78 Page 3 of 12

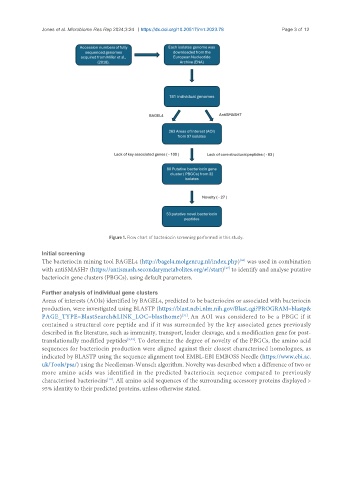

Figure 1. Flow chart of bacteriocin screening performed in this study.

Initial screening

[26]

The bacteriocin mining tool BAGEL4 (http://bagel4.molgenrug.nl/index.php) was used in combination

[27]

with antiSMASH7 (https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/#!/start) to identify and analyse putative

bacteriocin gene clusters (PBGCs), using default parameters.

Further analysis of individual gene clusters

Areas of interests (AOIs) identified by BAGEL4, predicted to be bacteriocins or associated with bacteriocin

production, were investigated using BLASTP (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastp&

PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome) . An AOI was considered to be a PBGC if it

[31]

contained a structural core peptide and if it was surrounded by the key associated genes previously

described in the literature, such as immunity, transport, leader cleavage, and a modification gene for post-

translationally modified peptides [9,29] . To determine the degree of novelty of the PBGCs, the amino acid

sequences for bacteriocin production were aligned against their closest characterised homologues, as

indicated by BLASTP using the sequence alignment tool EMBL-EBI EMBOSS Needle (https://www.ebi.ac.

uk/Tools/psa/) using the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm. Novelty was described when a difference of two or

more amino acids was identified in the predicted bacteriocin sequence compared to previously

characterised bacteriocins . All amino acid sequences of the surrounding accessory proteins displayed >

[10]

95% identity to their predicted proteins, unless otherwise stated.