Page 9 - Read Online

P. 9

Page 4 of 8 Kobayashi et al. Mini-invasive Surg 2020;4:30 I http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2574-1225.2020.12

A B

C D

E F

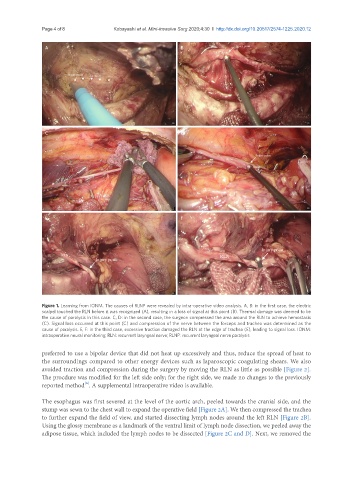

Figure 1. Learning from IONM. The causes of RLNP were revealed by intra-operative video analysis. A, B: in the first case, the electric

scalpel touched the RLN before it was recognized (A), resulting in a loss of signal at this point (B). Thermal damage was deemed to be

the cause of paralysis in this case. C, D: in the second case, the surgeon compressed the area around the RLN to achieve hemostasis

(C). Signal loss occurred at this point (C) and compression of the nerve between the forceps and trachea was determined as the

cause of paralysis. E, F: in the third case, excessive traction damaged the RLN at the edge of trachea (E), leading to signal loss. IONM:

intraoperative neural monitoring; RLN: recurrent laryngeal nerve; RLNP: recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis

preferred to use a bipolar device that did not heat up excessively and thus, reduce the spread of heat to

the surroundings compared to other energy devices such as laparoscopic coagulating shears. We also

avoided traction and compression during the surgery by moving the RLN as little as possible [Figure 2].

The procdure was modified for the left side only; for the right side, we made no changes to the previously

[6]

reported method . A supplemental intraoperative video is available.

The esophagus was first severed at the level of the aortic arch, peeled towards the cranial side, and the

stump was sewn to the chest wall to expand the operative field [Figure 2A]. We then compressed the trachea

to further expand the field of view, and started dissecting lymph nodes around the left RLN [Figure 2B].

Using the glossy membrane as a landmark of the ventral limit of lymph node dissection, we peeled away the

adipose tissue, which included the lymph nodes to be dissected [Figure 2C and D]. Next, we removed the