Page 42 - Read Online

P. 42

Sendino et al. Cancer Drug Resist 2018;1:139-63 I http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/cdr.2018.09 Page 141

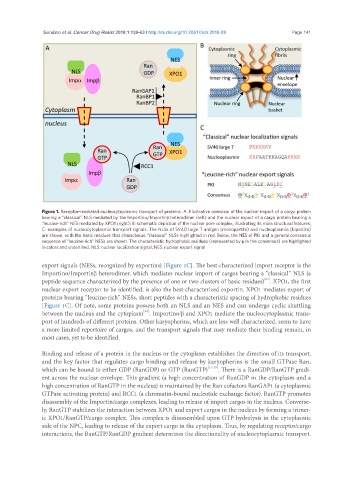

Figure 1. Receptor-mediated nucleocytoplasmic transport of proteins. A: Illustrative overview of the nuclear import of a cargo protein

bearing a “classical” NLS mediated by the Importina/Importinb heterodimer (left) and the nuclear export of a cargo protein bearing a

“leucine-rich” NES mediated by XPO1 (right); B: schematic depiction of the nuclear pore complex, illustrating its main structural features;

C: examples of nucleocytoplasmic transport signals. The NLSs of SV40 large T antigen (monopartite) and nucleoplasmin (bipartite)

are shown, with the basic residues that characterize “classical” NLSs highlighted in red. Below, the NES of PKI and a general consensus

sequence of “leucine-rich” NESs are shown. The characteristic hydrophobic residues (represented by f in the consensus) are highlighted

in colors and underlined. NLS: nuclear localization signal; NES: nuclear export signal

export signals (NESs, recognized by exportins) [Figure 1C]. The best-characterized import receptor is the

Importinα/Importinβ heterodimer, which mediates nuclear import of cargos bearing a “classical” NLS (a

[23]

peptide sequence characterized by the presence of one or two clusters of basic residues) . XPO1, the first

nuclear export receptor to be identified, is also the best-characterized exportin. XPO1 mediates export of

proteins bearing “leucine-rich” NESs, short peptides with a characteristic spacing of hydrophobic residues

[Figure 1C]. Of note, some proteins possess both an NLS and an NES and can undergo cyclic shuttling

[24]

between the nucleus and the cytoplasm . Importinα/β and XPO1 mediate the nucleocytoplasmic trans-

port of hundreds of different proteins. Other karyopherins, which are less well characterized, seem to have

a more limited repertoire of cargos, and the transport signals that may mediate their binding remain, in

most cases, yet to be identified.

Binding and release of a protein in the nucleus or the cytoplasm establishes the direction of its transport,

and the key factor that regulates cargo binding and release by karyopherins is the small GTPase Ran,

which can be bound to either GDP (RanGDP) or GTP (RanGTP) [17-19] . There is a RanGDP/RanGTP gradi-

ent across the nuclear envelope. This gradient (a high concentration of RanGDP in the cytoplasm and a

high concentration of RanGTP in the nucleus) is maintained by the Ran cofactors RanGAP1 (a cytoplasmic

GTPase activating protein) and RCC1 (a chromatin-bound nucleotide exchange factor). RanGTP promotes

disassembly of the Importin/cargo complexes, leading to release of import cargos in the nucleus. Converse-

ly, RanGTP stabilizes the interaction between XPO1 and export cargos in the nucleus by forming a trimer-

ic XPO1/RanGTP/cargo complex. This complex is disassembled upon GTP hydrolysis in the cytoplasmic

side of the NPC, leading to release of the export cargo in the cytoplasm. Thus, by regulating receptor/cargo

interactions, the RanGTP/RanGDP gradient determines the directionality of nucleocytoplasmic transport.