Page 9 - Read Online

P. 9

Best et al. Hepatoma Res 2021;7:32 https://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2021.52 Page 3 of 6

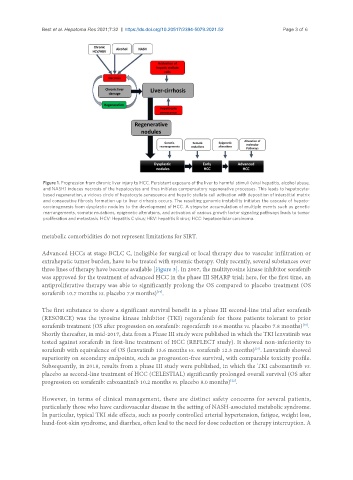

Figure 1. Progression from chronic liver injury to HCC. Persistent exposure of the liver to harmful stimuli (viral hepatitis, alcohol abuse,

and NASH) induces necrosis of the hepatocytes and thus initiates compensatory regenerative processes. This leads to hepatocyte-

based regeneration, a vicious circle of hepatocyte senescence and hepatic stellate cell activation with deposition of interstitial matrix

and consecutive fibrosis formation up to liver cirrhosis occurs. The resulting genomic instability initiates the cascade of hepato-

carcinogenesis from dysplastic nodules to the development of HCC. A stepwise accumulation of multiple events such as genetic

rearrangements, somatic mutations, epigenetic alterations, and activation of various growth factor signaling pathways leads to tumor

proliferation and metastasis. HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

metabolic comorbidities do not represent limitations for SIRT.

Advanced HCCs at stage BCLC C, ineligible for surgical or local therapy due to vascular infiltration or

extrahepatic tumor burden, have to be treated with systemic therapy. Only recently, several substances over

three lines of therapy have become available [Figure 3]. In 2007, the multityrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib

was approved for the treatment of advanced HCC in the phase III SHARP trial; here, for the first time, an

antiproliferative therapy was able to significantly prolong the OS compared to placebo treatment (OS

sorafenib 10.7 months vs. placebo 7.9 months) .

[19]

The first substance to show a significant survival benefit in a phase III second-line trial after sorafenib

(RESORCE) was the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) regorafenib for those patients tolerant to prior

sorafenib treatment (OS after progression on sorafenib: regorafenib 10.6 months vs. placebo 7.8 months) .

[20]

Shortly thereafter, in mid-2017, data from a Phase III study were published in which the TKI lenvatinib was

tested against sorafenib in first-line treatment of HCC (REFLECT study). It showed non-inferiority to

sorafenib with equivalence of OS (lenvatinib 13.6 months vs. sorafenib 12.3 months) . Lenvatinib showed

[21]

superiority on secondary endpoints, such as progression-free survival, with comparable toxicity profile.

Subsequently, in 2018, results from a phase III study were published, in which the TKI cabozantinib vs.

placebo as second-line treatment of HCC (CELESTIAL) significantly prolonged overall survival (OS after

progression on sorafenib: cabozantinib 10.2 months vs. placebo 8.0 months) .

[22]

However, in terms of clinical management, there are distinct safety concerns for several patients,

particularly those who have cardiovascular disease in the setting of NASH-associated metabolic syndrome.

In particular, typical TKI side effects, such as poorly controlled arterial hypertension, fatigue, weight loss,

hand-foot-skin syndrome, and diarrhea, often lead to the need for dose reduction or therapy interruption. A